Why doesn’t my team remember what I say?

Why doesn’t my team remember what I say?

You explain it clearly.

You answer the questions.

You leave the room thinking, right, that’s done.

The familiar leadership frustration

This is one of the most frustrating experiences in leadership. Especially when the message matters. A change in direction. A new way of working. The start of something important you genuinely care about. You’ve been thinking about it for weeks, maybe months. You’re invested. You’re clear. You’re ready to go.

And yet the energy you felt when you shared it doesn’t seem to last. Engagement fades. Momentum stalls. You start to question whether people were ever really listening in the first place.

At this point, many leaders tend to turn their frustration inward. Am I not clear enough? Am I boring? Am I expecting too much? Or they turn it outward. Why can’t people just remember? Why do I have to keep repeating myself?

Here’s the reassuring truth.

This isn’t a motivation problem.

It isn’t a competence problem.

And it isn’t a leadership failure.

It’s a human one.

Forgetfulness at work isn’t a sign that people don’t care. It’s a sign that brains are doing exactly what brains do. They forget things quickly and efficiently, unless something helps them hold on.

Once you understand that, the whole problem starts to feel less personal and much more solvable.

The forgetting curve explained

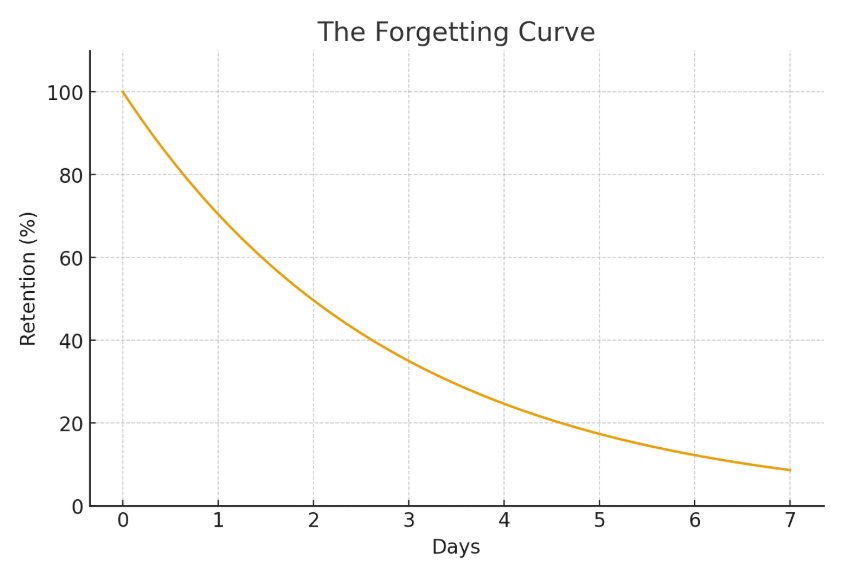

This is where the forgetting curve comes in. And once you’ve seen it, you can’t unsee it.

The forgetting curve was first mapped in the late 1800s by a psychologist called Hermann Ebbinghaus. It’s beautifully simple. On the vertical axis, you’ve got retention. On the horizontal axis, you’ve got time. Day one through to day seven.

Bit Famous works with businesses and organisations to help them communicate with confidence.

By Penny Haslam

MD and Founder - Bit Famous

FREE resources for leaders and people professionals from Penny Haslam and Bit Famous

Share this page

Where people professionals share the great work they do!

On day one, just after you’ve told someone something, retention is close to 100%. They can remember what you said. They might even repeat it back to you. It feels reassuring. You think, great, that’s landed.

But then look at the curve as the days pass.

By the end of the week, retention has dropped dramatically. Down to around 10%. Not because people are careless or disengaged, but because memory fades unless it’s reinforced. What’s left is often a vague sense that something was mentioned, without the detail, the nuance or the confidence to act on it.

In practical terms, this explains so much of what we experience at work. Why training sessions feel successful on the day but don’t translate into changed behaviour. Why big announcements lose energy so quickly. Why you hear, “I thought it was something like…” rather than, “Yes, I know exactly what we’re doing.”

The curve also explains why leaders are often out of sync with their teams. You’ve been living with the idea for weeks. You’ve thought it through. You’ve joined the dots. For you, it’s settled knowledge. For everyone else, it’s brand new and already slipping away.

When you look at the graph, the problem becomes clear. Saying something once simply isn’t enough. Not because you’ve failed, but because memory is fragile. If you want something to stick, you have to work with the curve rather than fight it.

And that’s where leadership communication really begins.

Why leaders underestimate forgetting

Most leaders underestimate forgetting for a very simple reason. They already know the message.

By the time you share something with your team, you’ve usually been sitting with it for a while. You’ve thought it through, refined it, worried about it, tested it in your own head. It feels obvious to you. Familiar. Almost boring. So when you say it once and see a few nods around the room, it’s easy to assume the job’s done.

This is where the disconnect creeps in.

Leaders often stop repeating a message not because it’s landed, but because they’re finished with it. Repeating it feels unnecessary. Even a bit patronising. There’s a quiet fear of sounding like you’re labouring the point or talking down to people.

But familiarity for you does not equal familiarity for them.

The forgetting curve doesn’t care how clearly you explained something or how important it is. It doesn’t respond to good intentions or well-crafted slides. It simply does what it does. Memory fades unless it’s reinforced.

There’s also a confidence trap here. When you’re clear on something, you assume clarity is contagious. It isn’t. Understanding has to be built, revisited and refreshed. Otherwise, people are left with fragments. A sense that this matters, without enough grip to act on it.

So when leaders think, I’ve already said this, the brain is thinking, this is already slipping away.

Once you recognise that gap, it becomes much easier to stop blaming yourself or your team. The solution isn’t to communicate louder or with more urgency. It’s to communicate with a better understanding of how memory actually works.

Repeat more often than feels natural

This is the bit that makes many leaders wince. Repetition feels clumsy. Heavy-handed. As though you’re nagging or overdoing it. There’s a point where you think, surely I’ve said this enough now.

But the forgetting curve tells a different story.

If memory drops off sharply after day one, then repetition isn’t optional. It’s essential. Without it, even the most important messages slide away before people have had a chance to do anything with them.

There’s a useful rule of thumb here. When you’re bored of talking about your message, it’s only just starting to go in for everyone else.

Think about how we absorb messages outside of work. Advertising doesn’t rely on a single appearance. You see the same campaign again and again. On billboards. At bus stops. Online. On TV. It’s not subtle, and it’s not accidental. Repetition creates familiarity, and familiarity creates recall.

Workplace communication works the same way. A one-off announcement, however well delivered, is the start of the process, not the end. If something matters, it needs to be revisited. Reminded. Reinforced. Often more times than feels comfortable.

That doesn’t mean saying the exact same words on repeat. It means keeping the message alive. Referencing it in different meetings. Linking it to decisions. Bringing it back into conversations once people have had time to live with it.

Leaders sometimes worry this will irritate people. In reality, it usually reassures them. Repetition signals importance. It tells people, this still matters, and I haven’t forgotten about it either.

When repetition is planned and purposeful, it stops feeling like nagging and starts feeling like leadership.

Use stories, not just stats

If repetition helps a message stay alive, stories are what help it stick.

At work, we often default to facts and figures. They feel safe. Professional. Objective. But the brain doesn’t hold on to them very well. Most people can listen to a perfectly sensible statistic and have no idea what to do with it five minutes later.

Stories or short anecdotes work differently.

When you share a human example, something shifts. People picture it. They feel it. Their brains light up in a way that dry information simply doesn’t. That emotional response isn’t a distraction from learning. It’s what drives it.

Research shared in the book Made to Stick makes this really clear. After hearing someone speak, around 63% of people remember a story, while just 5%remember a statistic. That gap alone should make us pause.

By anecdotes, I don’t mean polished stories or dramatic narratives. No one needs shaggy dog stories or a laboured “once upon a time” with a beginning, middle and end. I mean short, real examples that bring your message to life. Something that happened recently. A colleague who tried something new. A moment that made you think, that’s a good example of what we’re talking about here.

These small, human moments do important work. They trigger emotion, which helps learning. They also create motivation, not just understanding. People start to connect what you’re saying to their own experience, which makes them far more likely to remember it when it matters.

So rather than adding more slides or more data, look for one simple, relatable example that illustrates your point. A few seconds of colour and context can do more than a page of bullet points.

WIIFM - What’s in it for me?

This is the part we often rush past, but it’s one of the biggest drivers of whether people remember anything at all.

People don’t forget because they don’t care. They forget because their brains are constantly filtering information. And one of the quickest filters is a simple, often unspoken question: how does this affect me?

If a message doesn’t connect to someone’s day-to-day reality, it slides down the forgetting curve even faster.

As leaders, we often communicate from our own vantage point. We know why something matters. We can see the bigger picture. We understand the long-term benefit. But the people listening are thinking about their own pressures, priorities and problems. That’s not selfish. It’s human.

The same message will land very differently depending on who’s hearing it. A sales team will listen through the lens of targets and relationships. Operations will be thinking about process and efficiency. Finance will be listening for risk and cost. HR will be thinking about people and impact. If everyone hears the same words but can’t see themselves in them, recall will be low.

This doesn’t mean changing the message every time. It means changing the angle.

When you take a moment to frame your message around what it helps them do better, worry less about or achieve more easily, you give their brain a reason to hold on to it. Relevance creates grip.

So before you communicate something important, ask yourself a simple question: why would this matter to them? When people can answer that for themselves, remembering becomes much easier.

Bringing it all together

When you step back and look at it, none of this is complicated. But it is easy to overlook.

Messages fade because memory fades. Not because people are difficult, distracted or disengaged, but because forgetting is built in. Once you accept that, the job of leadership communication becomes much clearer.

Repetition keeps a message alive. Anecdotes help it stick. Relevance gives people a reason to care.

These aren’t separate techniques. They work best together. Repeating a message that feels human and personally relevant doesn’t feel like nagging. It feels helpful. It reassures people that they’re on the right track and that this really does matter.

This is also where confidence comes in. Leaders who understand how memory works stop second-guessing themselves. They stop blaming their teams. They communicate with more calm, more intention and far less frustration.

Instead of asking, why don’t they remember? The question becomes, how can I help them remember?

And when you make that shift, communication stops being a one-off performance and starts becoming a steady, confidence-building process. One that gives your message a fighting chance of surviving the forgetting curve and turning into action.